OUR ETHNIC BACKGROUND

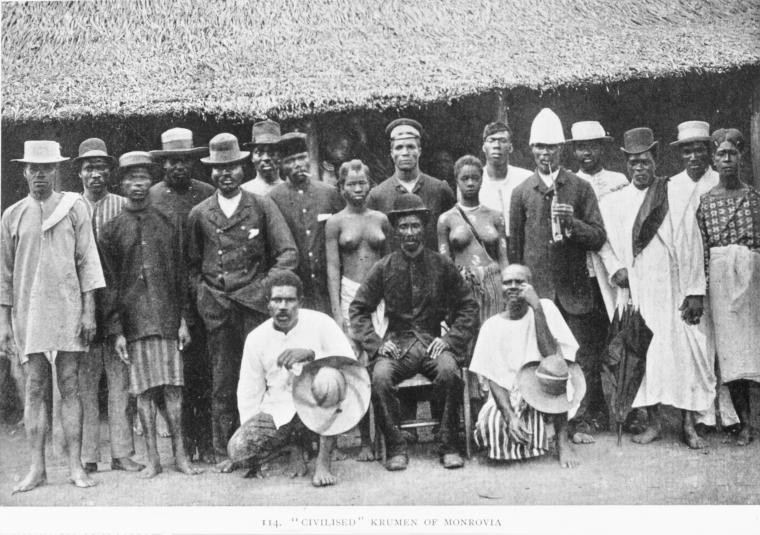

As stated previously, the Nyanfore and Nimley family is of the Kru ethnic group. The Kru, linguistically, is composed of the Bassa, Grebo, De, Belle, Krahn, Sapo and Kru. Originally in Liberia, they are said to have occupied the Folgier kingdom, which extended from the area now called Monrovia to the St. Paul River. From Folgier, the Kru gradually migrated southeastward into the coastal areas.

The Kru tribe was and still is, divided into dakos, or subgroups. They include the Gbitao, Jlao, Karboh, Boou, Sikleo, Niffu, Betu, and Jlokqwa. The dakos migrated into the various coastal parts of Liberia at different periods and were ruled by kings or elders. The dakos are divided into pantons or clans whose heads are usually members of the dakos decision-making body.

In the past, the Kru were warriors and are still warriors by nature and spirit. They are known to express their minds freely and to stand up for their principle and value, as observed by others. One great Kru warrior was King Sokwalla, a general, who is said to have ruled a large part of Coastal and Eastern Liberia, then called Grain Coast in the 1530s. Another warrior was Juah Nimely, “the wonderful Nimely”, who fought and died for justice in the 1930s. The Kru had fought many battles. Example, they revolted in 1915-1916 against impunity and taxation without representation. And in 1930-36, they battled against military revenge and aggression of the central government in the Sasstown War, in which Juah Nimley and other warriors fought. Despite US military assistance, army men, and gunboat to the government, the Sasstown people fearlessly fought back and bravely refused to surrender. The war lasted more than five years. Background of the war might be of interest.

The war started because the Barclay government retaliated against the Sasstown Kru. In the 1920s, the Charles B. King administration was accused of forced labor and slavery practice against native people in a plantation in Fernando Po, a Spanish colony in Africa. Some of the laborers and those who died on the plantation were Kru and Grebo people. King and his Vice President Allen Yancy resigned due to a public and international outcry of the practice. President Edwin Barclay succeded King, but in Barclay administration in the 1930s, the League of Nations began an investigation into the Fernando Po case. The inquiry found the King government guilty of forced labor and that King and Yancy received kickbacks for the practice. The League, therefore, leveraged penalty on the Liberian government. Barclay regime responded by revenging on those who testified against the government and on those who championed the cause.

The Jlao people, called the Sasstown people, were among the advocates with its chief, Juah Nimley. The government military with US support burned Sasstown villages and according to a report, "81 men, 49 women, and 29 children died when the huts were burned ...." Many of the victims were said to be chiefs. But as pointed out, the Sasstown people did not sit supinely; they fought back. Juah Nimley became a national hero. President Barclay saw him went he was brought to Monrovia as international reporters interviewed him after the war. "After months of exile in Gbarnga, he returned to Sasstown and later died there and became a legend".

The Kru individually have traveled to different parts of the world. In late 1800, a Kru Prince named Samuel Kaboo Morris came to America in 1893 at the age of 18 on his own and settled in Indiana. As a boy in Liberia, he was taken into captivity. His father, a Kru king, could not pay enough for his ransom. He escaped to a plantation where he met a white missionary who taught him how to read, about Jesus, and about America. Kaboo traveled by boat to the US.

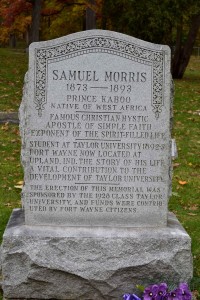

Kaboo wanted to become a missionary so he would return to Liberia to serve his people. Educated at Taylor University, then called Fort Wayne College, in Fort Wayne, Indiana, he was an inspirational minister, preaching to his fellow students, faculty and community members, Blacks and Whites. Unfortunately, he died from pneumonia fever in 1893, only two years in America at the age of 20.

Taylor University has a memorial in his name. He inspired American society in an age of plantation slavery and racial oppression, suppression, and prejudice in America. Kaboo was loved and missed by the town and people. His biographer, Lindley Baldwin, writes about Kaboo funeral. "The burial ceremony in Lindenwood cemetery, his last earthly resting place, was attended by a multitude such had never before accompanied there."

Kaboo may have been the first or one of the first Kru to migrate to America.

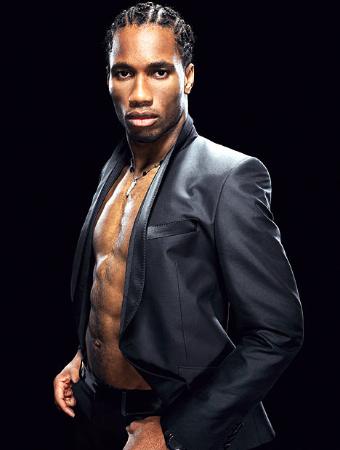

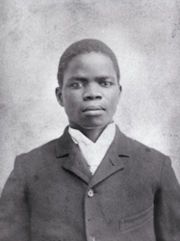

Didwho Welleh Twe was another famous Kru. In fact, he was a legend and was considered the greatest of all the Kru political giants. In addition to his educational achievements, his assistance to P.G. Wolo, and membership with the American Political Science organization, he was the first of the native Liberians to openly seek the Liberian presidency.

“Twe was a former representative in the Liberian Legislature. (He) had a distinguished mark on his forehead, culturally identifying him as a Kru”. Because of his advocacy in the Fernando Po matter and against other injustices in Liberia, he was expelled from the legislature. He was the political leader of the United People Party, which later became the Reformation Party; and he became the party standard bearer in the 1951 election with running mate Tyson Wood of Grand Bassa. But the ruling True Whig Party government, the standing party in Liberia then, denied his party from registering, stopped him from running, arrested and jailed key members of his party and forced him into exile to Sierra Leone. Before his exile, he told his followers and the Liberian people that the True Whig Party government will not be in power forever and that the true leadership of Liberia will come from the East.

Though he was a skillful politician, he did not publically and prematurely expose himself without first having the basis; before entering politics, he was a commissioner and a wealthy man, owning many acres of land in the area called then and now, “the Twe Farm” in Duala, Monrovia. As a student in America, he was sponsored by a US representative, a senator, and by Samuel Clements, literally known as "Mark Twain". He was educated at a prep school and at Harvard and Columbia. Twe was nationally and internationally known.

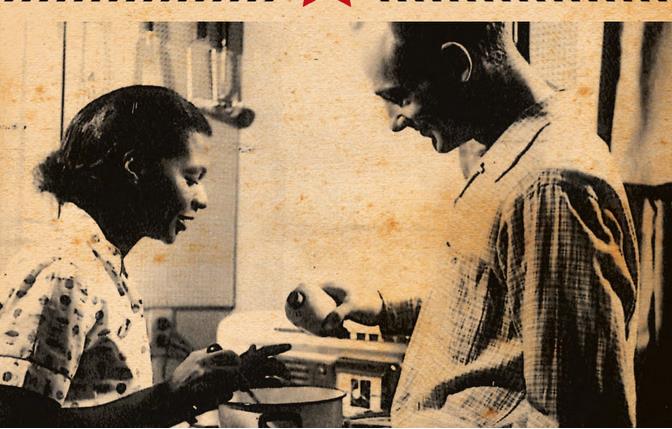

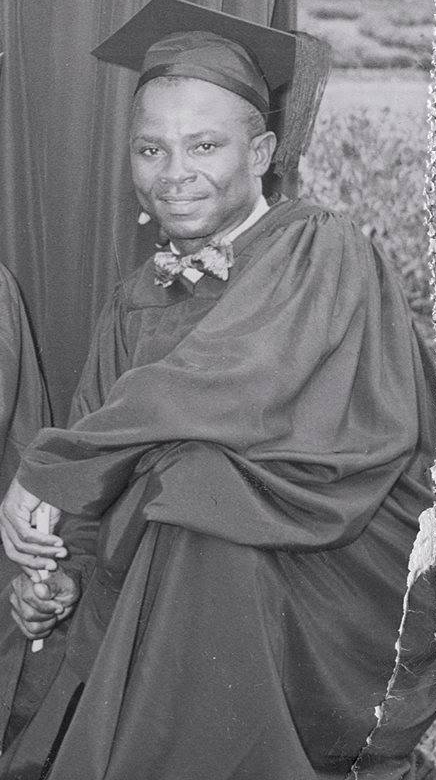

Twe’s key political advisor for the 1951 election was Dr. Thorgues Sie, Sr., a Grandcess son who returned from America to help run Twe campaign. He was the national chairman of the party. Sie lived in America for many years. He was an anthropologist, a scholar, and an advocate. He married Rachel when he was a student at Morgan State University, which was during Thorgues’ days called Morgan College in Baltimore, Maryland. The couple born Hortense Sie and Thorgues Sie, Jr.

Hortense, known as Tee, attended New York University School of Films and edited the film, “Spotlight on South Africa”. Among her friends was the famous athlete, singer and freedom fighter Paul Robeson. He attended the showing of the film. She married Lowell Beveridge, who had graduated from Harvard University and was a graduate student at Columbia University in New York. Lowell, who was White, was a progressive, and later became an editor of “The Crisis” magazine, which stood for justice and civil rights in the U.S in the 1920s. W.B. Du Bois, a pioneer advocate of the civil rights struggle, originally edited the paper.

In 1924, Thorgues Sie, Sr., while in the US, reported to the magazine regarding the Liberian issue during the Charles King presidency. On August 21 that year, Du Bois apologized to Sie for not replying early, but if Sie would give hard facts to the issue, “we might be able to use it”, Du Bois responded.

As a student in Liberia, Sie was a classmate of President William Tubman. In the US as a student, he was a member of the African Students Association of America, and Canada and a key speaker at the Association's symposium concerning World War II. Other speakers at the conference included Francis Nwia-Kofi Nkrumah, according to the program speaker list. Interestingly, the name just stated was the original name of Kwame Nkrumah, who later became the first prime minister and president of Ghana. In his profession, Sie contributed to many scholarly works in anthropology. This information together with other data would suggest that native Liberians were qualified to become leaders of their country but were not given the opportunity seemingly due to ethnic prejudice.

In Liberia in 1950, James Nyanfore, Sr, listed Thorgues Sie as a reference in his Cuttington College application. Sie was also the agent of Grand Landing Company in Monrovia. Indeed 1950 was one year before the 1951 election. Moreover, sixteen years later in 1966, Nyanfore’s son Dagbayonoh met Sie in Monrovia while Dagbayonoh was about to travel to the US for school. Sie gave him a letter introducing him to Tee as a relative. Dagbayonoh met Tee, her husband Lowell and Tee’s brother junior in Brooklyn, New York. Lowell appeared to be a quiet man, spoke softly. He talked about research, which Ambassador Christie Doe either did or discussed on the Kru living in the hills of Jamaica.

Tee may have followed her father’s footsteps, for she was an advocate and participated in freedom causes as a young lady. Like her dad, she met future leaders and freedom fighters such as Kwame Nkrumah. She also traveled to Europe to attend a youth advocacy conference.

In some of her letters to her father, while he was in Liberia, it was said that she expressed the desire to visit Liberia. But that did not happen; Thorgues may have been too preoccupied with the Liberian problem. His health was declining after years of harassment, intimidation, and imprisonment from the Twe incident. He died shortly after 1967.

Another Grandcess born was Bishop Pekro Gray, a Pentecostal Bishop who permanently lived in America. It is not known the exact time he went to the US. Probably he may have come to the country in the early 1900, the same time Doe Nimely and Thorgues Sie arrived. Like Nimley, he worked as a laborer on the construction of the New York subway. He later engaged in religious work and established the Abbosso Apostolic Faith Church in Liberia, Nigeria, and America. The American church was in Harlem, New York City. In Liberia, the church, which is generally called the Grandoe Church, still exists in New Krutown.

The church had branches in other parts of Liberia, for example, in Butaw, Sinoe County, and Grandcess, now part of Grand Kru County. Bishop Arthur Grandoe was from Grandcess and so was the just-deceased Bishop Karfee Panton. Prior to Grandoe, the church was headed by Pastor W.R. Herrick. Pekro married Josephine and born Helen and David. He died about 1969 in the US.

Bishop Gray paved the way for many Grandcess children to America. He brought Mahkan Doe Smith (Martha Smith) as a little girl and facilitated the way for Nyudueh Morkonmana and Dagbayonoh to come to the US. Martha is a Nyanfore, daughter of a nephew of Dagbayonoh Nyanfore. Her mother was Bishop Gray’s sister. Martha married Smith in New York. She born six children, including Sharon, Derrick, and Eric. Morkonmana, who later became speaker of the Liberian House of Representatives during the Taylor administration, married Barbara and born two daughters, Baleh and Nadee, in America before returning to Liberia.

When the history of Liberian progressives of the 1970s is completely written, the name Togba-Nah Tipoteh will take center stage. He is the father and architect of the struggle for rights and justice during that period. Born of a Kru parentage of social privilege in Monrovia, Liberia, he left for higher studies in the US and obtained a doctoral degree in Economics at 27. He returned to Liberia but did not forget his roots. He learned to speak Kru, his native language. He gradually changed his name from Rudolph Roberts to Togba-Nah Roberts to finally Togba-Nah Tipoteh, the original and traditional name of his father, who as a boy, was a ward of Robert Manneh and therefore took Robert’s name. The father was referred to in the community as Robert’s boy, a behavior of the Liberian ward system where the servant took the master’s name. Before 1980, English names were preferred over African names. Liberians with African names were generally considered "country", uncivilized, and of a native background.

Tipoteh’s exercise was a self- criticism, a cultural and social transformation; the first step to self- revolution and liberation. By this process, one can correctly inspire and sensitize others for a change. He saw himself as a messenger, the Kru meaning of Tipoteh. He took a teaching post at the University of Liberia after working briefly at the Bureau of Budget. He wore slippers made of car tire, a symbol of the poor; and it became a fashion called “The Tipoteh Slippers”. In association with other concerned Liberians, he advocated for justice specifically for poor people and low-income workers. This led to his dismissal at the university.

He and other progressives, including Dew Tuan-Wleh Mayson, Amos Sawyer, and Boima Fahnbulleh, in the mid-70s founded SUSUKU, a combination of Susu and Ku, a traditional community development concept, involving the pooling together of financial resources and the coming together of people to help each other. About two years later, they organized the Movement for Justice in Africa (MOJA), an advocacy group. Though the name Africa was used strategically, the group focused on justice for poor and disadvantaged people in Liberia. The plan worked as some of the elite joined the cause for Africa, and the Vice President of Liberia then became an official and supporter of SUSUKU. The progressive effort and sensitization of the 70s helped motivate uncommissioned soldiers of the Liberian military to topple the Tolbert regime in 1980. The change led to the present multi-party democracy in Liberia. Tipoteh became minister of planning and economic affairs in the new administration. He continued his advocacy after the military government.

In the ending months of the Liberian civil war, he engaged in the disarmament of the combatants earning him “Politician of the Year”, and “The man on the Ground” by the media after the crisis. His involvement in community awareness in the Ebola epidemic in his country adds to his profile.

Some observers saw Tipoteh as the second coming of Didwho Welleh Twe. There are certainly similarities. Their respective parents came from Sinoe County of the Niffu and Nana Kru sections of the Kru tribe. Tipoteh is from the Tarloh panton of the Niffu dako. Both men upon obtaining higher education returned home and did not forget their roots. They engaged in advocacy and lost their jobs. Their movements were popular composing of others. When Twe died, Tipoteh’s father, Pastor Samuel Roberts, preached for the occasion. It was an honor for the selection.

Differently, however, Twe possessed the needed material resources; his followers were largely older Liberians and his cause was mass-based, while Tipoteh focused on the youth, mostly university students impressed also with the intellectualism and revolutionary speeches of the key progressives. Further, Twe sought political power, but Tipoteh called for justice and did not have the financial base for his movement. But both leaders operated in a different period and time, and that could have impacted the difference.

Togba-Nah Tipoteh ran unsuccessfully three times for the Liberian presidency. Nevertheless, he continues his advocacy and is widely respected for his legacy.

We will discuss more of Twe and other Kru in the preceding paragraphs. We will also talk about our Kru culture.

Teniwenti Toh was one of the forces for change in Liberia. He was a leader of Liberians in the Diaspora for socio-political transformation in Liberia in the 1970s. Born in Liberia of the Sasstown Kru origin, he left for the US in the early 60s for advanced studies after education at Saint Patrick High School in Monrovia. He was popularly known in Monrovia as Wellington Toh. He obtained a Master’s degree in English Literature and Urban Studies in America. He was an excellent writer with a strong command of English grammar and wrote many articles.

But Teniwenti’s greatest contribution was not his writing ability, but his revolutionary attitude toward the cause of the Liberian people, particularly Kru people. In 1973, he organized AWINA, meaning in Kru our voice. “It was an organization of the Kru ethnic group in America and Canada. But its general goal was to serve as a vehicle for the organization of indigenous Liberians for radical and progressive advocacy on Liberia affairs, particularly native issues”. Several months later, under his direction, AWINA was incorporated with branches in many states of America. He effectively used the pen to express the cause of his people and country. As others have said, he sincerely lived up to his name Teniwenti, which means in Kru, “the issue never ends”. To him and others, “in the cause of the people, the struggle continues”.

After a careful review of the Liberian issue and condition under President Tolbert, AWINA on March 14, 1975, staged a peaceful demonstration in front of the Liberian Embassy in Washington, DC calling for democratic change in the country. In the organization manifesto written mainly by him for the demonstration, AWINA informed the world of the organization purpose and position on Liberia. “We organized to address the general issue of native suppression and repression in Liberia. We believe that only through a radical approach would the regime in Liberia take us seriously and improve the condition for all Liberians. As a revolutionary organization, AWINA is dedicated to helping liberate Liberia from Black Colonialism. We view the struggle as the people’s struggle, because “the people and only the people alone are the motives in the making of history,” the document said.

Under Teniwenti’s leadership, AWINA became a powerful progressive organization in the Diasporas on the Liberian issues. Its Washington demonstration was the first in the Diaspora against the settler regime and set the pace for future demonstrations by Liberians abroad. Also, AWINA set the tone for other Liberian progressive organizations that followed, including MOJA and the Progressive Alliance of Liberians (PAL). In 1979, the Union of Liberian Association in the Americas with AWINA members held the largest demonstrations near the White House in Washington, DC and at the UN in New York respectively against the Tolbert government. AWINA under Teniwenti and other Liberian organizations in America were the external and supporting arms to local advocacy groups, specifically MOJA. AWINA's publication organ was the AWINA Drum, a news magazine edited and published by Dagbayonoh Kiah Nyanfore ll and assisted by Siahyonkron Nyanseor.

Like Togba-Nah Tipoteh’s similarities with D. Twe, Teniwenti’s behavior was like that of legendary warrior Juah Nimley. Both men, of Sasstown roots, were fearless and uncompromising with those whom they considered enemies of their people. While Juah Nimley fought with arms, Teniwenti battled with the pen as a weapon and his organization as an army.

Teniwenti Toe returned to Liberia and later served as the auditor general of Liberia in the Taylor administration. He died in Liberia in 2003. At his funeral, Nyudueh Morkonmana, a former official of AWINA, spoke on behalf of the organization. AWINA Drum editor-publisher from the US represented the paper and paid tribute to the fallen hero.

S. Tugbe Worjloh, Sr. is another Kru son deserves mentioning in the contemporary history of the struggle of common people in Liberia. Unlike those stated above, Worjloh was not well known and did not make the headlines of the Liberian dailies during the struggle in the 70s; and he did not enjoy the glory of the 1980 revolution either, "but he was one of the progressives, and he was really a good one too". As a boy, he was an advocate and a quiet warrior for justice from his days in a Sanquine village in Sinoe County to Claratown in Monrovia as a young adult. He was a journalist, AWINA Drum African bureau chief, "writing and reporting about events in the country. He was fearless, he was prepared to go to jail for his writing". His social consciousness and advocacy at an early age set him apart from the established icons of Liberian progressivism of the 70s. Moreover, though he was older than most of them, he was humble, a foot soldier and did not try to overshadow them. He was also a historian and contributed greatly to the book, "THE KRU", a documentary history of the Kru people. He was called the walking encyclopedia for his knowledge of historical facts and the possession of personal handwritten documents on the tribe. Worjloh was the vice governor of New Krutown in Monrovia, a position he held before his death in December 2017. He was 81 years old.

Didwho Welleh Twe, Plenyono Gbe Wolo, Thorgues Sie, Juah Nimley, Togba-Nah Tipoteh, and Teniwenti Toh had one thing in common;

they all maintained their African identity, their traditional African names, in their respective struggle for justice. They did so in the face of temptation

and pressure to do otherwise. Many African freedom fighters did the same; example, Kwame Nkrumah, Jomo Kenyatta, Amilcar Cabral, and Ahmed Sekou Toure. As stated before, self-identity, cultural pride, nationalism, and the overcome of fear are some of the initial steps to liberation.

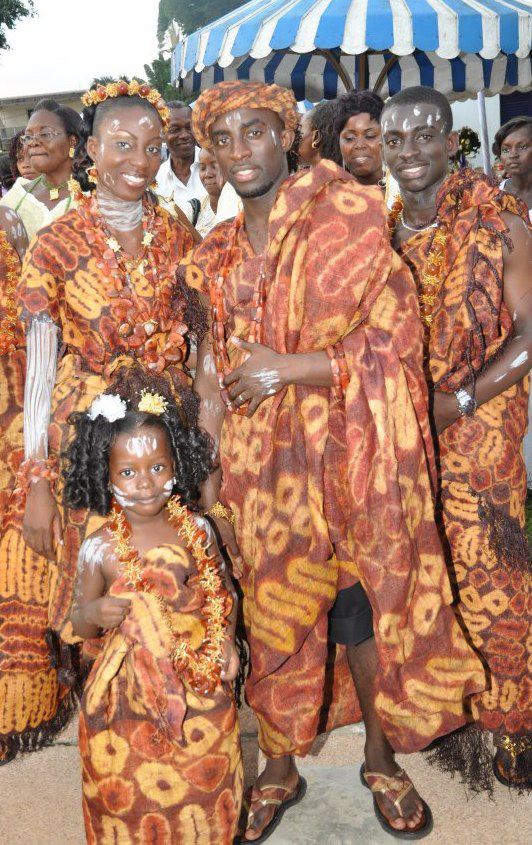

CULTURAL BELIEFS

Traditionally, the Kru believe in the universal God, the creator. He is called Nyeswa. Additionally, there were other Gods who were considered agents of the Almighty. Like ancient Greeks, they were oracles whom the people appealed to for help. For instance, there were Gods for war, birth, and futile land. Historians and other experts on the Kru state that the Sikleo consulted Pepa for war. Ki Jirople was considered the main spirit and oracle whom most Kru dakos called on regarding matters. He was believed to live in the Putu mountains and was with the Jedlepo people known as Betu. They were said to have the strongest spirit and to possess the most powerful spiritual medicine among the Kru.

Next or equal to Ki Jirople was Veto, God of War, whom the Betu, Karboh, Nuon, Gbeta, and the Niffu were believed to have consulted. Unlike Ki Jirople, Veto may have resided in the forest. These Gods were considered the direct messengers of Nyeswa, the creator, whom all Kru know and worship to this date.

The ancestors were also agents of the almighty and could be called upon to help the descendants. There was and still is a general belief that the heavenly God knows and sees everything and what we do in the dark will come to light. The good we do will never go unrewarded. It will be rewarded plentifully either to us or to our family, and so the evil we do; it will come back to us or to our family. These beliefs are not only with the Kru but also with other people. Moreover, traditionally, the Kru or African religious belief regarding the living God and his messengers is the same as we Christians believe in God and in his son, Jesus. Both groups believe in the spirituality of God and in the existence of the oracles.

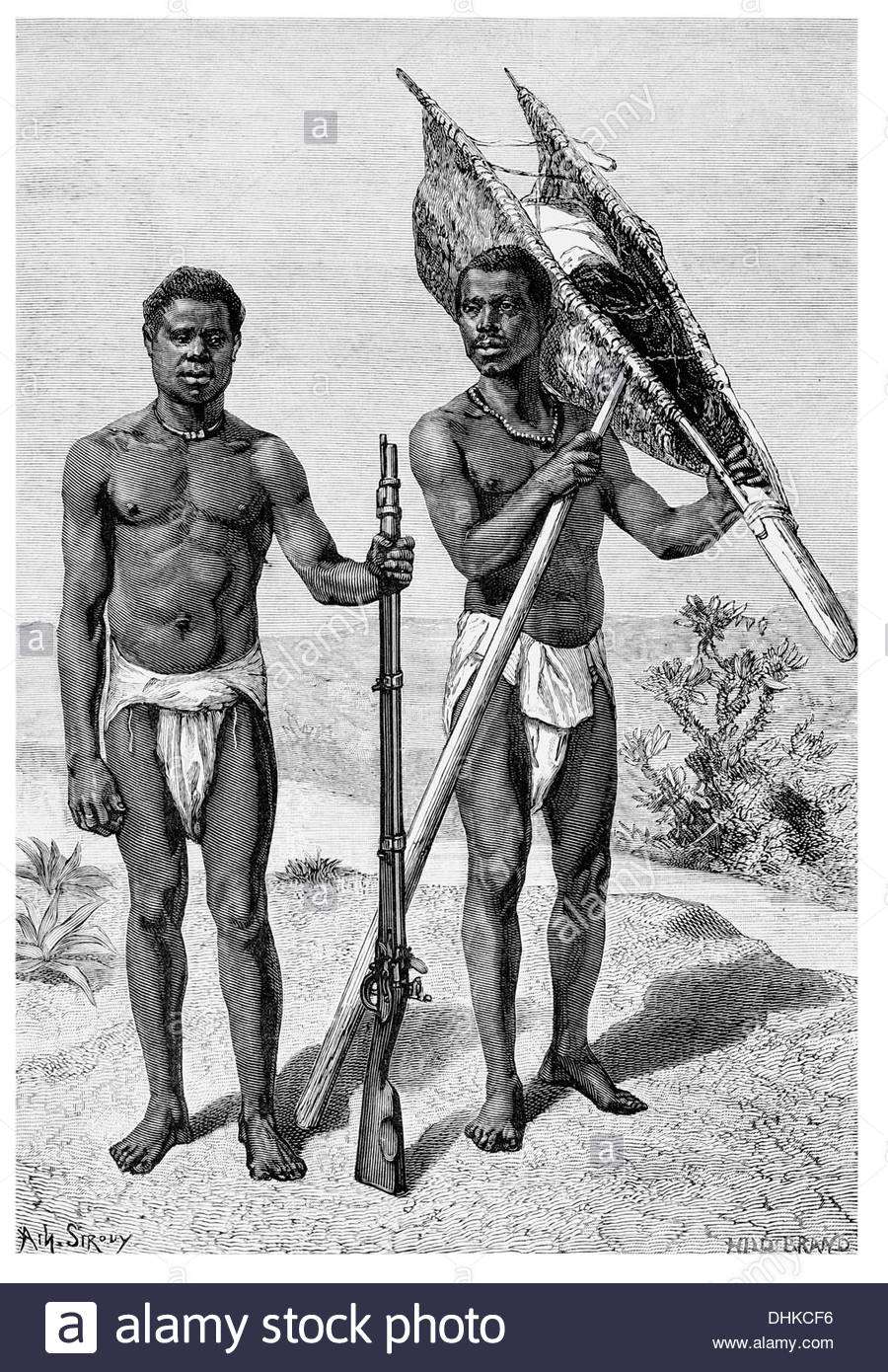

There were inter-tribal disputes and wars among the Kru. The land was the main reason for fighting. Gbo was the training unit for war preparation. The gbobi, the father of the gbo, headed this unit. Gbo also performed war dance during burial ceremonies. Some members dressed in leopard skins and danced with spears and shields. As indicated before, young Nyanfore and Nimley were members of gbo. The dogbio led the military or army to war. The gbowulio served as spokesman for the army and addressed the elders on military issues. During a war, the women and children were placed in Ji-wo, meaning “tiger mouth”, the house of the bodio, the high priest, for safety and protection. It was a sacred place.

A document pointed out that also during a war, the Tugbewa, the keeper of records, was the last to leave the village and the first to enter the village after the battle. Accordingly, he kept the record of the war, the number of soldiers, number dead, and number wounded. He did not participate in the battle but hid somewhere and watched the fight. He carried a drum, which he beat to inform his men for help or defense when an enemy approached him. He also took with him a weapon for self-protection. He also carried a bag of kernels presenting the number of his soldiers. If one died, he removed a kernel from the bag to symbolize the fallen comrade.

Melville Herskovits, an anthropologist and a pioneer of Black Studies in the US, wrote below about Tugbewa and confirmed the above story of the role of Tugbewa.

"During the battle, he keeps the record of wounded or fallen soldiers, as he did at the initiation of his age grade, by keeping the bag with palm kernels (ta or tawa), filled at the time of initiation. It is said that he keeps this bag with him all the time and even uses it as a pillow at night; each time a warrior is killed, the tugbewa takes out a seed and informs the gbobi. Before a man's death, it is believed, his palm kernel will crack and thus inform the tugbewa about imminent death. Tugbewa himself does not enter battle but remains in a safe, elevated place near the sacred town drums (tu-ku) in order to watch the battle. He has to defend himself with a sharp knife (su kpè) against enemies since the enemy will be able to roll up the battle from the rear if he is killed. He, therefore, is near the drums which he will beat when the enemy approaches him".

The late Tarty Teh said that in some wars, the side with fewer casualties was declared the winner. In such a case, the goal of the fight is not to kill many people but to show which group is stronger and more skillful in fighting.

The Kru are generally friendly. But as a principle, they do not like people take advantage of them. In their response to disadvantage, they are unfortunately and negatively branded as mere "fighters" or "troublemakers". People also misinterpreted Kru culture of age- grouping of a big brotherhood called "babi”. In this culture, the older members become big brothers to younger or junior members. For example, a boy of 15-20 years old becomes a big brother to 10-14 years old boy. The babi protected the smaller brother and served as a role model. But others, who did not understand Kru tradition, viewed babi negatively as big-stupid, dull, uneducated, tough-looking and low-class. This negative perception brings us back to Didwho Welleh Twe, his party, his followers, their struggle, and how this factor affected Kru people in general.

Regrettably, this stereotype affected some Kru youngsters growing up in the cities up to the 1970s. The feeling escalated in 1951 during the D. Twe presidential campaign when the government reacted negatively to his candidacy. The regime singled out the Kru as troublemakers and being uncooperative. Consequently, many Kru perhaps desirous of or wanting to retain their government jobs denied their ethnic identity for fear of the reaction. They encouraged their children not to be known as Kru. Additionally and generally, such stereotype and cultural negativity forced many tribal youths to negate their ethnic background for acceptance into the Western culture and society of the settler ruling class.

However, many Kru, including Thorgues Sie, Wesley Wiah Wisseh, Nimene Botoe, Bo Nimley, Doe Bopleh, Robert Slewion Karpeh, W.W. Nimley, Teacher Jugbe, and others who backed Twe and stood up for their right, principle, and pride suffered severely. As other observers noted, the government harassed and hunted them in a Gestapo fashion by its security operatives, specifically Deputy Police Commissioner Tecumbla Thompson, a fellow Kru. The victims were jailed before the 51 Election, even though their party was denied participation in that election, and even though their leader was forced out of the country. Their main lawyer was disbarred by the Supreme Court. Thompson and Cummings Seyon, another Kru, were said to have reported them to the government.

In their jail cell, the victims asked themselves why were they arrested and imprisoned, apparently in reference to their rights as citizens to form a political party, canvass, vote, and complain against any unfair and unlawful election practices. The government in court charged them with sedition, alleging that the party wrote President Tubman, the UN, the US government, and other international bodies complaining about the election; and in so doing, the party invited foreign entities into the domestic affair of Liberia with the intention of destabilizing the country and government. They denied the charge, but the court found them guilty and sentenced them to multiple years. Although they appealed to the Supreme Court, the high court in 1954 affirmed the ruling.

Like his key followers, Twe's life was not safe. Juah Wiah Wisseh, his bodyguard, dressed him as a woman at night and moved him from one place to another. Sometimes he was buried alive with a small hole or opening just for seeing and breathing. On one occasion, the sands fell into his eyes. "He was in serious pain", said Tarloh Twe Patterson, Twe's daughter, in an interview with James Nyanfore, Sr's son Dagbayonoh in 1973. "The government soldiers were coming to the house; there was no good place to hide him, so we hurriedly buried him; I felt sorry for dad, he suffered too much", Tarloh added.

But also there were Kru who did not support Twe mainly because of his Nana Kru background, a part of the Kru in Sinoe considered by others as inferior or bush Kru and therefore lacking the education and ability to lead. This thinking was unfair to Twe and seemingly prejudicial: though his parents were from Nana Kru, he was a Liberian and was born in Monrovia. His parents' place of birth had no bearing on the presidency. As a citizen, Twe reached out to other Kru dakos, including the educated members of the tribe. His support to P.G. Wolo and strong association with Thorgues Sie of Grandcess were examples of his outreach effort. Further, his party was broadly based, consisting of members of other tribes and of the Congo Liberians.

Twe's opponent, then sitting President William Tubman, used the "internal Kru crash" for political advantage. A Liberian historian observed. "Tubman maintained that Twe was not a real Kru and did not have the support of the majority Kru people... Tubman began influencing well known Kru people from established Kru sections, including Grandcess, Picnicess, Sasstown, and Sanguine. They are the seacoast Krus with many educated people, most of whom were desirous of government jobs. Tubman was successful in the strategy as many educated Krus began denouncing Twe. They felt that Twe as a lesser Kru and did not deserve to be President".

The above created a relatively split in the early 1950s between those Kru considered Twe's supporters and those viewed as regime collaborators. But in subsequent years, particularly after Tubman's death in 1971, the division completely stopped.

One factor which contributed to the unity could have been the 1980 revolution, resulting in the overthrow of the settler regime of the True Whig Party. With the change, the Kru Coast Territory became Grand Kru County, hence empowering the people and politically upgrading the Southeast region. Twe's prophesy of the demise of the True Whig Party came to pass, and he was once again celebrated. A newly constructed school was named posthumously in his honor. It was called D. Twe High School in New Krutown, Montserrado County where he was born. Part of District 16 of the county was named in a tribute to him. Moreover, the PRC, the new government which seized power, also built the Redemption Hospital, a referral medical facility in New Krutown. The town became a respected and political subdivision of the county and is one of the largest communities in Liberia. Twe died in the early 60s upon his return from exile.

The genesis of the Kru-Settler conflict can be traced to the coming of the ex-slaves from America to Liberia in the early 1800s. Unlike other Liberian tribes, the Kru have traveled the world and felt that the settlers were not better than they. With the settlers' view of cultural superiority over native people and the determination to rule, the former slaves encountered greater resistance from the Kru resulting in the hostility or the bad blood between the two. Thus to the settler ruling elite, D. Twe's "audacity" to seek the presidency was an affront.

The Kru also may have known or observed that the freed slaves from America were generally illiterate. Tom Shick's study on emigration to Liberia from 1820-1843 shows that the majority (about 70%) of the ex-slaves could not read or write. Emigration continued from 1843 to the 1860s, including the settlement of several American ex-slaves and immigrants from the West Indies, and the arrival of about 1400 Congos. The settler population in the first period reduced about 63% from 4851 to 1819 due largely to a high death rate, according to the study. Taking Shick's estimates and that of the latter, the illiteracy rate for the combined periods could be over 90%.

The Congo settlers arrived in Liberia from the 1820s-1860s basically naked. They were brought on captured slave ships. It was said that natives on the coast provided them with clothing upon arrival. Hence, to the Kru, the settlers were not superior as claimed.

As a tribe, the Kru experienced out-migration from Liberia in the years after WW1. The Fernando Po crisis together with the Sasstown War and the D. Twe incident mentioned led in part to the migration of some Kru to other West African countries, notably Nigeria, Ghana, and Sierra Leone. Many of the immigrants were from Grandcess. For instance, James Nimley and Nyanfore Boryonoh, and David Nyanfore, son of Dagbayonoh Kiah Nyanfore, settled in Sierra Leone, Ghana, and Nigeria respectively. James and Boryonoh returned to Liberia later but David did not.

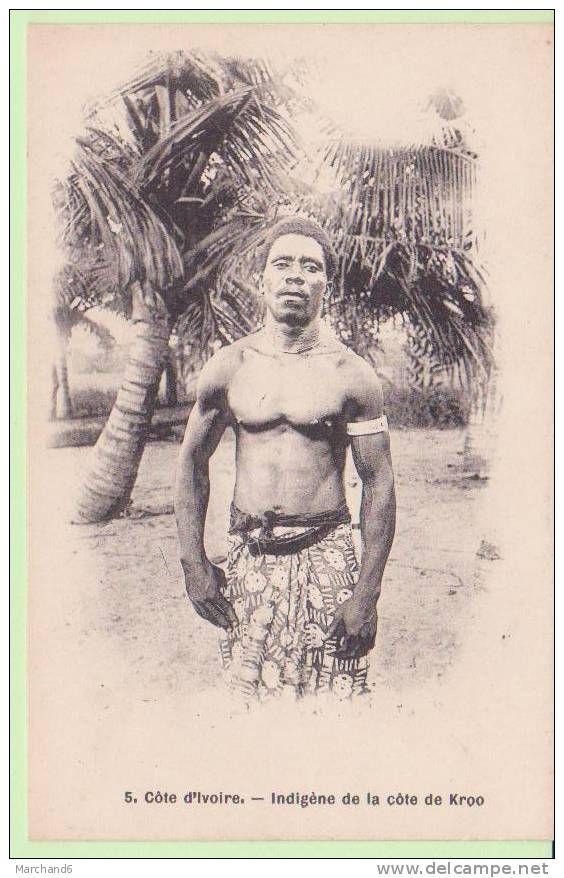

The Kru in Ivory Coast are native Ivoriens maintaining their Kru culture. There are also Krahn and Grebo Ivoriens. The Krahn particularly are largely in Midwest Ivory Coast and are called Guerre. While Sierra Leone had an established and continued community of Liberian immigrants, Ghana appeared to have more Liberians than Nigeria. But Ghanian Prime Minister Kofi Busia 1969 order expelled Liberians including other foreigners out of the country. Before and during the order, few of the Grandcess returnees went back to Grandcess but most stayed in Monrovia. Many of the Kru returnees were professionals with skills in bookkeeping, accountancy, and teaching. Others were soccer players, such as Jackson Weah and Jasper Wleh, two of the famous Liberian soccer stars in the 50s and 60s.

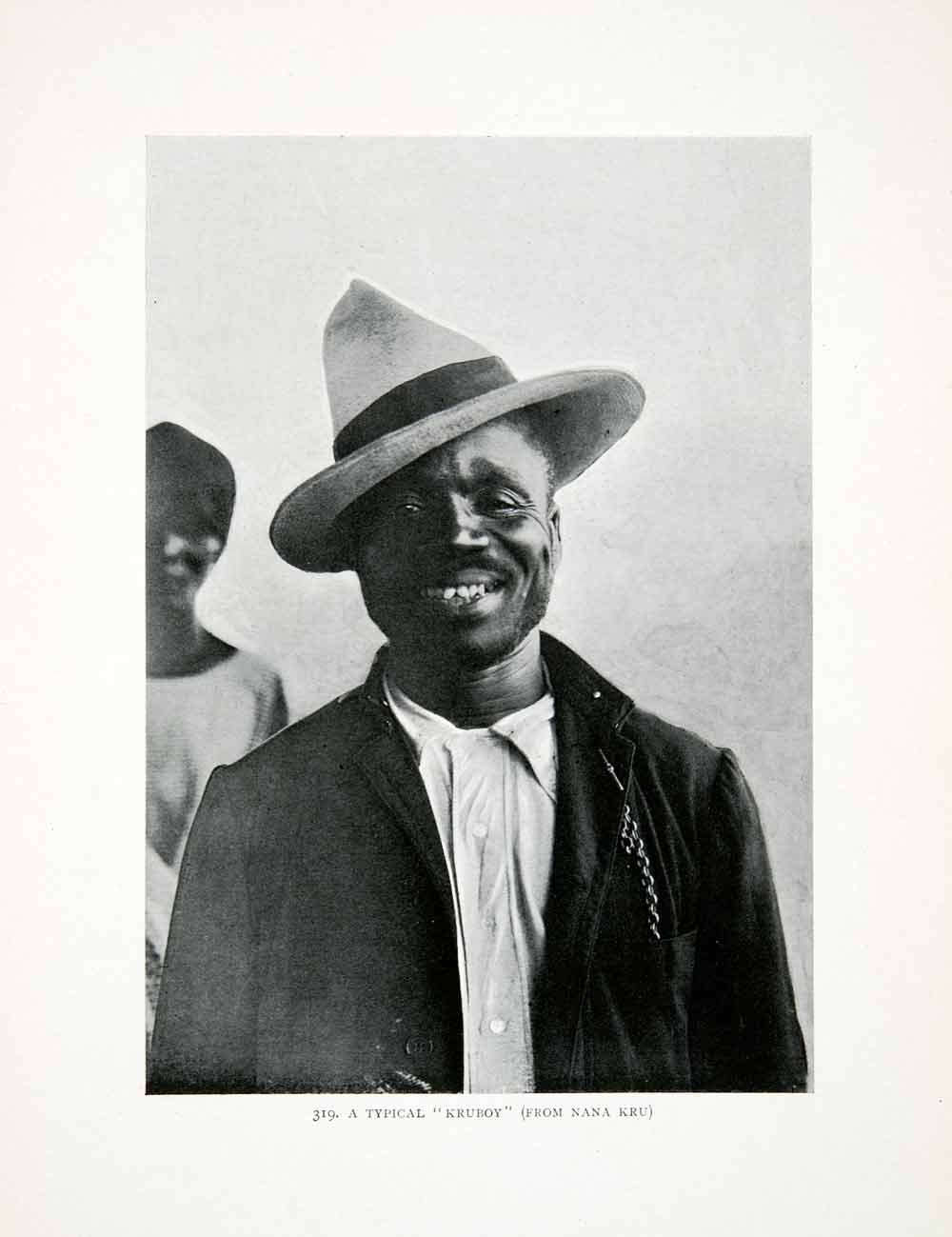

Kru men are mostly fishermen. They were also seafarers. Some served in the Royal Navy during World War II. Because of their work on ships and their adventure, as stated before, many have traveled over the world and have settled and helped build communities outside of Africa. Poet Maya Angelou acknowledged the contribution of the Kru in her poem, "On the Pulse of Morning", which was read at the first inauguration of President Bill Clinton in 1993.

Besides immigration, as seafarers, the Kru worked on cargo ships traveling to other West African countries, particularly Nigeria and Ghana, known then as Gold Coast. The trip took two or three months. The work provided the crew with their main income. Their return after travel was a happy homecoming.

In our discussion on Grandcess, we talked about the role ship work played in the economy of Grandcess and why King Nyepan sent a delegation to Great British interest during World War 1. Ports of crew recruitment may have been competitive as many Kru coast and Monrovia residents needed work on ships. Monrovia was the major center of recruitment. Some crew stayed or later migrated to their ports or countries of work. Gold Coast was one of the countries. The period was before independence when the countries were under colonial rule and the shipping lines were under foreign control.

Among the Kru in Liberia and perhaps in Ghana it was said that the biological father of Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah was a Liberian Kru seafarer. But neither Nkrumah autobiography nor his biographers confirmed this expression. However, internationally known sociologist Stanislav Andreski wrote in “African Predicament” that “Nkrumah’s actual father was a Kru seaman from Liberia”. Nkrumah was a nationalist and a Pan Africanist. Andreski indicated that it would have been politically suicidal had Nkrumah acknowledged that his father was a foreigner and not a Ghanaian. Like in the case of D. Twe, his political opponents would have used it against him as not being a real ethnic Ghanaian. But since Nkrumah’s death, no official publication has been written regarding his true father.

Nkrumah was raised by his mother, Elizabeth, a poor market woman and was named after a family member. His father’s real name was unknown. Young Nkrumah had two recorded dates of birth. He changed his name as he got older and became politically active and revolutionary. When Thorgues Sie knew him in America, he was Francis Nwia-Kofi and not Kwame. The Kru in Liberia celebrated him as one of theirs when he visited Liberia in 1958 as head of state. It was also said that in the Gold Coast, his father was known and referred to as Kruman, a name changed to Nkrumah which the son used. But these events may probably be mere instances and did not prove that he was Kru. The change of name could be the result of self -awareness and the desire to seek life purpose and destiny.

During the slave trade, the Kru were known “for fighting for their freedom, reducing their value to slave traders who found them too difficult to control for slavery. If captured, the Kru would simply kill themselves, rather than become properties”, says D.L. Chandler of Black History Facts.

Click below link to hear more about the Kru on Black American Web.com.

https://blackamericaweb.com/2017/02/01/little-known-black-history-fact-kru-people/#.WvnzzLIK6Cs.

KRU PERSONALITIES

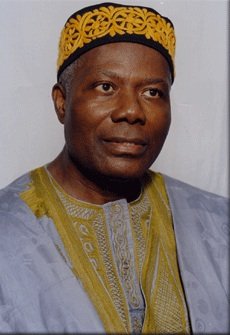

DIDWHO WELLEH TWE

THORGUES SIE’s DAUGHTER TEE AND HER HUSBAND LOWELL

Samuel Kaboo Morris

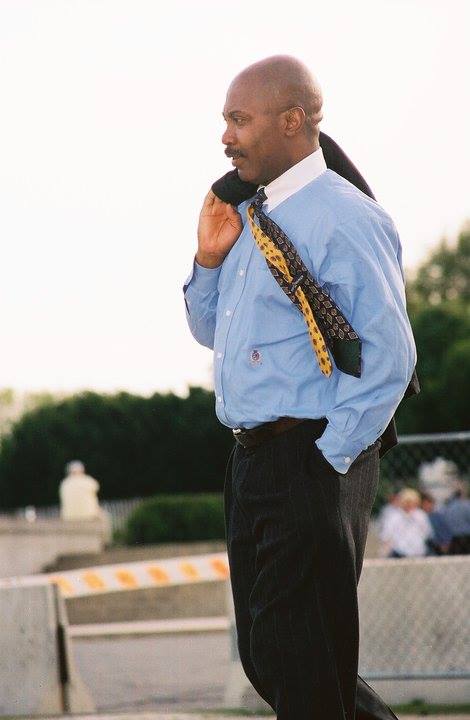

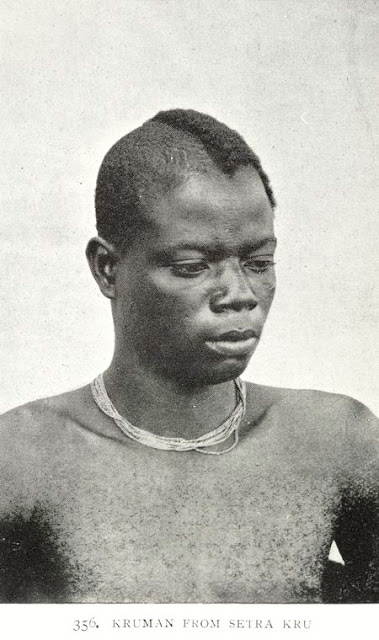

A kru sailor

GET IN TOUCH WITH US

.jpg?etag=%22f7a7-5b1ab556%22&sourceContentType=image%2Fjpeg)

%20-%20Copy.png?etag=%224f5876-5b1d6a78%22&sourceContentType=image%2Fpng&ignoreAspectRatio&resize=500,714)

_Plenyono_Gbe_Wolo.jpg?etag=%2231ba0-5afd8447%22&sourceContentType=image%2Fjpeg&ignoreAspectRatio&resize=400,667)

.jpg?etag=%225d00-5bbc8e7a%22&sourceContentType=image%2Fjpeg)

.jpg?etag=W%2F%224d3f-5be49cfb%22&sourceContentType=image%2Fjpeg)